How did the universe evolve? What laws govern the universe? Are there extra dimensions? How can we search for dark matter?

These are all questions that experiments at the world’s largest (and most expensive) science laboratory tries to answer.

This summer, I had the opportunity to travel to Geneva, Switzerland so I could participate in some research at the world’s largest particle physics research center - CERN (European Council for Nuclear Research).

Founded in 1954, the experiments at CERN draw collaboration from physicists and engineers all over the world. CERN’s mission is to provide state-of-the-art particle accelerator facilities that enable world-class physics research and exploration of new science and technology.

While I was there to do a research project regarding some data compression algorithms, I was also able to see many of the massive scientific instruments, such as the detectors, up close and learn so much about the engineering and science that goes into the experiments.

Standard Model Crash Course

To understand why CERN needs to accelerate particles to nearly the speed of light, let’s first discuss some physics.

Did you know that a proton and a neutron are actually comprised of even smaller particles known as quarks? Quarks, along with leptons, are the two types of elementary particles that make up the matter around us. The best known lepton is the electron.

In addition to the matter, we also experience forces in our universe: the electromagnetic force, the gravitational force, the strong force, and the weak force.

We have all experienced the electromagnetic force and the gravitational force, but the strong force and weak force work at very short ranges and are only relevant at the subatomic level. The strong force actually binds the quarks together in protons and neutrons, while the weak force is responsible for particle decay, when one type of subatomic particle turns into another.

Of these forces, three of them have force carriers, which are particles that act as messengers to mediate an interaction between other particles. For the electromagnetic force, it is the photon. For the strong force, it is the gluon. For the weak force, it is the W and Z bosons. Gravity has a hypothesized force carrier called the graviton but it has not yet been discovered.

To complete the Standard Model, there is one more particle called the Higgs boson. This particle gives mass to other particles. It was actually detected at CERN in 2012!

Together, these fundamental particles and forces (except gravity) make up the Standard Model, which describes how these particles relate to and interact with one another.

At CERN, physicists and engineers work together to study the tiny particles that make up everything around us. They are the building blocks of matter! We study them so that we can learn more about the laws of nature regarding how the universe operates.

Accelerating Particles

In order to explore what actually makes up matter, we need a way to break down that matter first. This can be done by accelerating particles to close to the speed of light and colliding them with one another. This releases so much energy that we can actually break apart matter into its fundamental particles!

At CERN, you can find particle accelerators to accelerate these particles and detectors to observe what happens at the collision point. CERN is home to the LHC (Large Hadron Collider), which is the world’s largest, most powerful particle accelerator.

The protons actually enter the LHC as hydroden, but they stripped of the electron, leaving behind a positively charge proton behind. Since these particles have charge, we can accelerate them using alternating electric charge! This is done through the LINAC (linear accelerator).

The accelerated particles will then enter the Proton Synchrotron Booster, the Proton Synchrotron, and the Super Proton Synchrotron, before entering the final Large Hadron Collider. Each of these rings uses an electromagnetic field to accelerate and bend the particles so they can eventually travel at 99.9999991% the speed of light. The size of the LHC? 27km or 16.5 miles of underground tunnel.

Finally, the particles are ready to be collided at one of many collision sites around the LHC, which are where the particle detectors - CMS, ATLAS, ALICE, and others - can be found.

Visiting CMS and ATLAS

This summer, I had the opportunity to visit two of the detectors - CMS and ATLAS. Both detectors have a large range of scientific goals, spanning from further probing our current model of particles and forces, to searching for dark matter and higher dimensions, to looking for new particles.

CMS stands for the Compact Muon Solenoid. It stands at 21 meters long, 15 meters high, 15 meters wide and weighs around 14,000 tons. It uses a powerful solenoid magnet to generate a 4T field (which is ~100,000 times the strength of Earth’s magnetic field)!

ATLAS stands for A Toroidal LHC ApparatuS. ATLAS stands at 46 meters long, 25 meters high, and 25 meters wide. However, it weighs only 7,000 tons, half the weight of CMS, and generates a 2T field, 2T less than CMS.

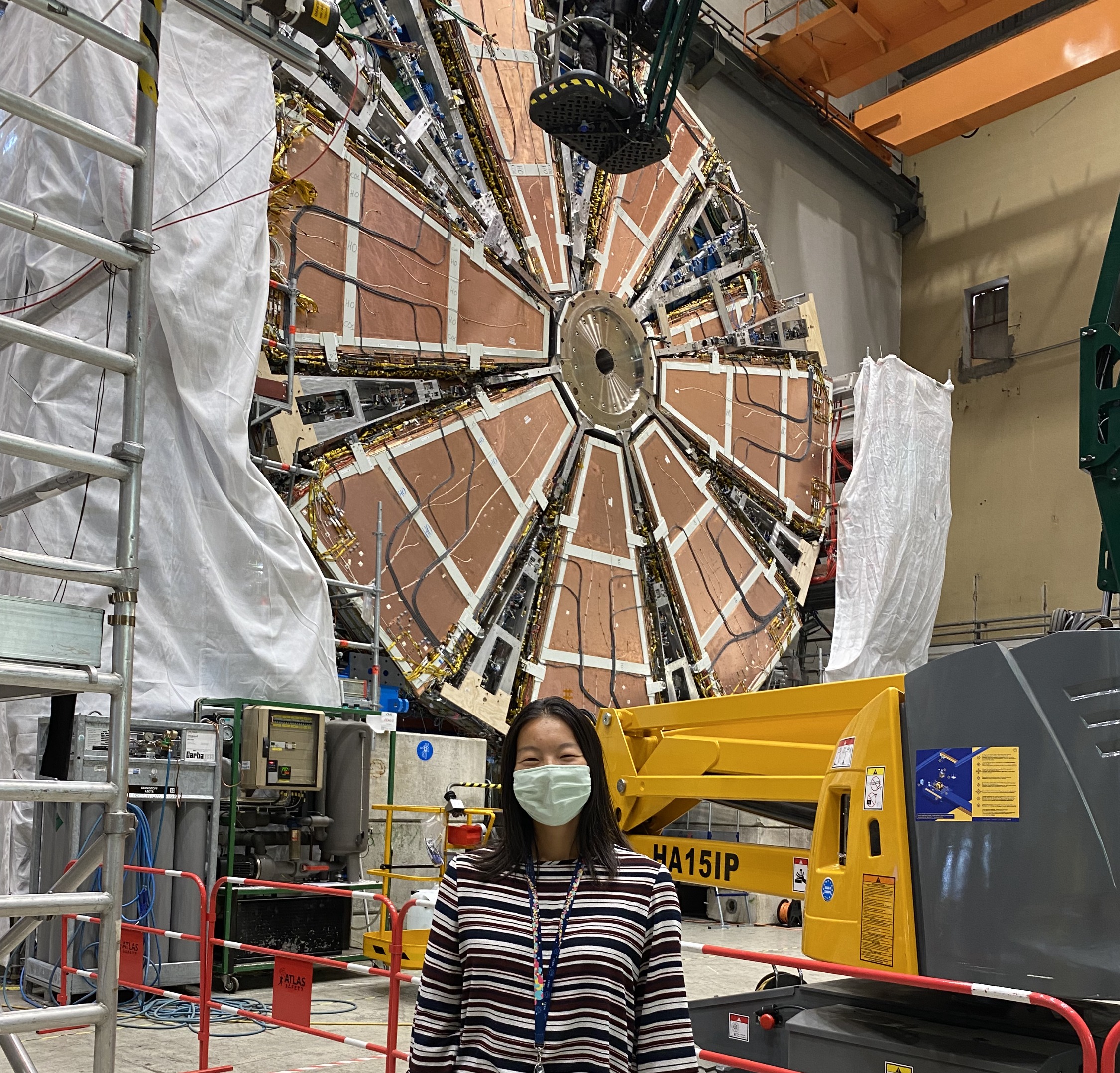

During one of my lunch breaks, I got to see the new “small” wheel of ATLAS under construction. It was actually quite large.

Both CMS and ATLAS have their strengths and weaknesses, but they operate in similar fashion. In both these detectors, a powerful magnet bends the charged particles from the collision, so we can measure the charge and momentum of the particle. Then, trackers measure the trajectory, or the track, of the particles and calorimeters measure the energy of the particles.

Finally, the muons come into play. Muons are part of the lepton family with electrons. You can think of the muon like the electron’s heavier cousin. In these experiments, there are detectors to observe muons and measure the momentum from the collision.

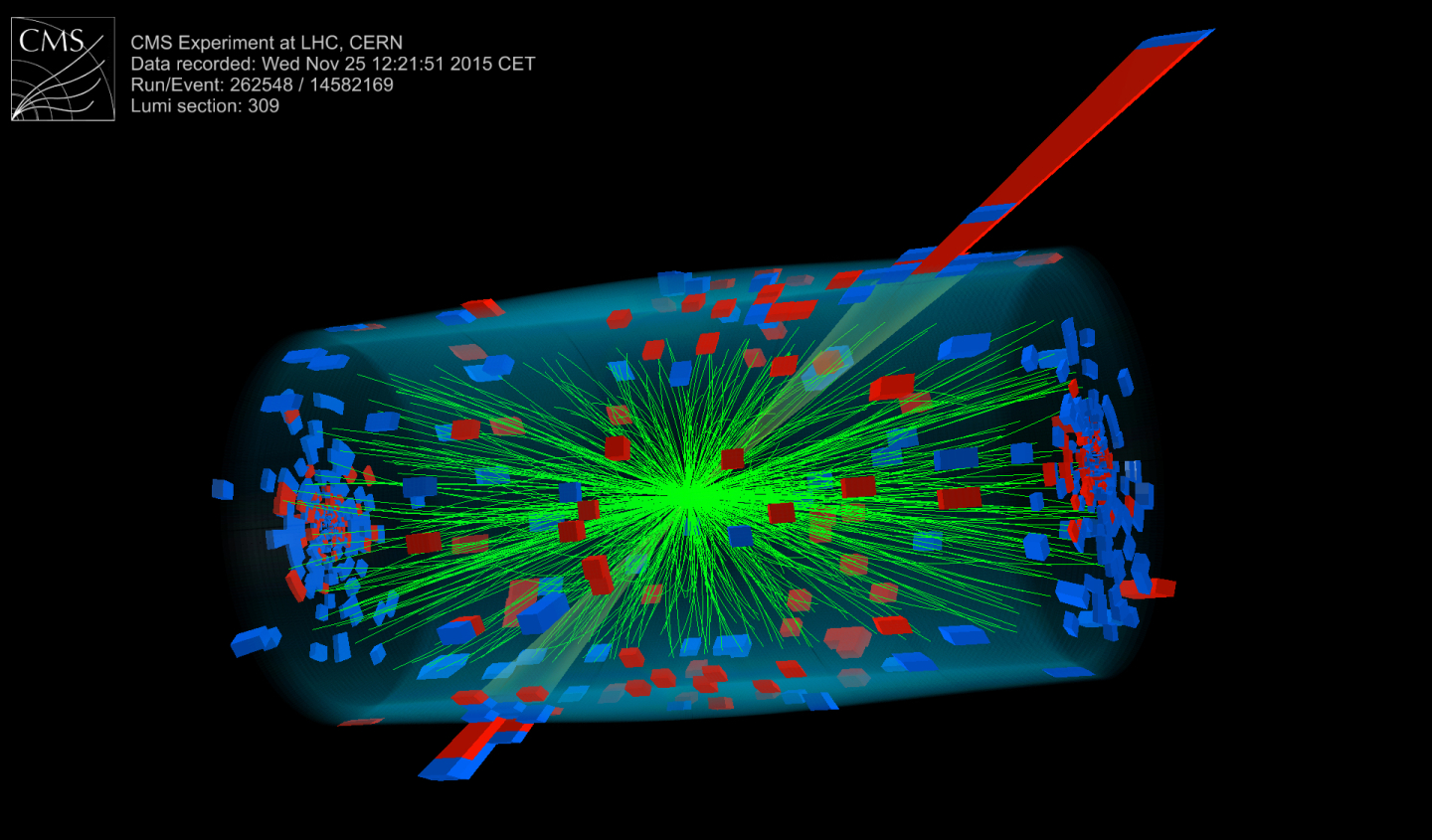

A reconstructed collision from one of these detectors looks something like this:

Computing at CERN

Finally, once the collisions occur, there is so much recorded data that needs to get stored. CERN’s Worldwide LHC Computing Grid system takes care of processing, storing, and analyzing all the data collected from the LHC. At Tier 0, the raw data is stored at the CERN data center and copied over to a data center in Budapest. From there, copies of the data get sent all around the world for storage, (re-)processing, and analysis.

As detector technology advances, we can collect more and more data from these experiments, but this is projected to occupy so much storage space, that we do not have the means to keep up. Currently, we already are petabytes range (1 PB is 1,000,000 GBs or 1,000 TBs).

One solution is data compression, which encodes or modifies the data in order to reduce the amount of space it takes up. This summer, I had the opportunity to work on a project assessing the performance of a new data compression algorithm!

Reflecting on an Incredible Experience

At CERN, I had the opportunity to see with my own eyes the massive scientific instruments that really push the frontiers of technology. Being able to witness first-hand the sheer size of the detectors, the complicated intricacies of every piece along the way, and the incredible feats of technology and engineering that make everything possible, that was truly eye-opening.

Sometimes, all I could think about was how in the world debugging happened!

Nonetheless, it was amazing being a part of a collaboration that tries to answer some of the hardest questions in the universe, like what is the universe truly made of and how does it work. While I did feel extremely small and humbled, I was also proud to contribute to something so much greater, with so much global, scientific impact.

I also had the opportunity to meet, and become friends with, so many brilliant minds at CERN. Everyone seemed to come from a different place in the world, converging here to dig deeper into a common goal: understanding the fundamental physics that governs our universe.

I became friends with people who worked on the vacuum, the magnet, theory, entrepreneurship, data, and the list goes on. Hearing about their projects, I realized that each of us is contributing such a small piece of the puzzle, but without our piece, the puzzle would not be complete. Every component had to come together to make the entire experiment work.

Truly it has been such an incredible opportunity to be here, to meet so many amazing people, to learn so much about physics and computing, to witness first-hand the feats of engineering, collaboration, science, technology that made all of this possible.

I left Switzerland with so much more than just an extremely rewarding experience working at one of the coolest places on Earth. I left with so many wonderful memories of smiles and laughter, excitement and adrenaline.

I am grateful to have met so many kind, inspiring, and welcoming people along the way, and I am honored to call them my friends. While two months is not too long, I feel like I have known them for a lifetime. Thank you all for making Geneva feel like a second home.

I hope we meet again someday, somewhere in the future.

Watch the video!